Both images found at: http://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/m/medical_training.asp

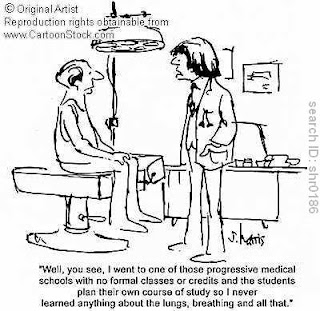

Both of the cartoon images above represent the ideas of medical knowledge and training. By providing a glimpse into the practice and curriculum of future physicians, we are surrounded by the idea of creating a “competent” and “caring” doctor, unlike those pictured above. The first image presents the importance of the medical curriculum and how future physicians should or should not be trained. The second image presents the practice of physician and how a physician’s knowledge and training is important in creating a “competent” doctor. In relating these images and both of the articles on “mediating”, I would like to discuss the importance of how medical knowledge is constructed and how the ideologies of health are shaped.

Byron J. Good and Mary-Jo DelVecchio Good’s article “ ‘Learning Medicine’: The Constructing of Medical Knowledge at Harvard Medical School”, studied three groups in the 1990 class at Harvard Medical School, the “New Pathway” curriculum, and the health sciences and technology curriculum. By concentrating on the training of physicians, they believed they could differentiate the “phenomenological dimensions of medical knowledge, on how the medical world, including the objects of the medical gaze—the students and the physicians—are reconstituted in the process, ad how distinctive forms of reasoning about that world are learned” (83-84). The findings of this study are provided in accordance to several themes that encompass medical training, such as:

1. “Medicine is science”. The first two years of the curriculum are emphasized as being science, because medicine is science. Science is factual based and is not affected by or based on value judgments.

2. “The person is the body”. The object of medicine is the individual person, primarily the body.

3. “Medicine is about ‘entering the body’”. Medicine gets inside of the body by case histories and lab exercises.

4. “ ‘Medical gaze’” and its view of the body reconstitute the person as object. In medical training, the student is conditioned to hold the conventional view of the body in a detached manner of seeing the human patient, and to study the view of the person-body.

5. “The ‘medical gaze’ reconstitutes the subject (the student)”. The student has to manage their objective gaze with society’s conventional view of the person-body.

The perspectives of the objective body and the human person, studied by medical students, hold a contradictory message in medical curriculum. The Goods article represents the curriculum as “the dual discourse” of “competence” and “care”. Competence is “associated with the language of the basic sciences, with ‘value-free’ facts and knowledge, skills, techniques, and ‘doing’ or action’” (Good, 91). This part of medicine is given priority because it is presumed as the basis of medical practice. Caring is “expressed in the language of values, of relationships, attitudes, compassion, and empathy, the nontechnical or as one student called it the ‘personal’ aspects of medicine” (Good, 91). This dual discourse creates a progression of dichotomies surrounding the qualities and problems of medical education on how to create “caring” and “competent” physicians.

In the article “Against Global Health? Arbitrating Science, Non-Science, and Nonsense through Health”, the author Vicanne Adams offers a “critical exploration of the processes by which the notion of ‘health’ in Global Health Sciences holds a tyrannical relationships to problems within the actual practices of global health” (40). The author argues that the conversations of “health” between doctors, patients, and politicians are not all talking about the same thing, in which the recognition of “health” is culturally constructed and socially sustained. The author gives us insight on the boundary between “science” and non-science”. In addition, the author discusses the debate on health in two ways. First, the author presents the cultural meanings of health and examines the ideologies that construct its meaning. Second, the author presents approaches in how to move forward, and to discover the principles behind “health”, in order to produce healthier interactions about our bodies.

In both articles we are presented with the notion that the study of medical knowledge and education is a comparative perspective. Physicians are an important source of information on how to achieve health and/or well-being. The roles of physicians need to be taken more persistently with a sense of humanity and a better eye for examining the patient holistically. I believe there needs to be a new message advocated by medical schools to physicians that goes beyond treating just the body, but takes a more holistic approach in diagnosing and treating a patient. The reason physicians should change how they view and diagnose a patient stems from the perspective that treating the body leaves out social, political, and economic variables of health. In order to create “competent” and “caring” physicians, the argument then is to start this paradigm shift of thinking in physicians when they are in medical school by changing the way physicians are educated to cure or improve a person’s health. The solution for physicians to balance out the needs of the physical body and the human person perspective of patients is to implement global health education on determinants of health and disease into medical school curriculums. Global health is important to medical knowledge and education because the demographic of patients is ever changing, multi-cultural, and diverse in many other ways. The world has become progressively more interconnected by the determinants of health and disease, including socioeconomic, environmental, and political factors, and globalization now affects almost everyone’s lives. An increase in the flow of people, goods, services, and information between countries has a powerful influence on the world’s health and health care. The global migration of people and products increases the threat of disease and highlights the connections in health and medicine. Today, the emergence of a new public health threat to individuals in one area of the world becomes a threat to all individuals throughout the world. Teaching the global aspects of medicine and understanding medical resources and care in a developing country will prepare physicians and give them a better understanding of health and medicine. In turn, this will make for better physicians and strengthen the health care system. In summary, newly trained physicians need to be well rounded on global health issues, understand emerging global diseases, and be cross-culturally sensitive, in order for medical schools to educate and create “competent” and “caring” physicians.

Sources:

Adams, Vicanne. “Against Global Health? Arbitrating Science, Non-science, and Nonsense through Health.” Against Health: How Health Became the New Morality. New York: University Press, 2010.

Good, Byron and Mary-Jo. Learning Medicine: The Constructing of medical Knowledge at Harvard Medical School. Knowledge, Power, and Practice. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

No comments:

Post a Comment