Thursday, January 27, 2011

Power and Organization in Medicine: Ayurveda and Biomedicine

“Ayurvedic medicine is all the rage in the west, but it's more than just a passing fad -- in India it dates back many thousands of years. Ancient wisdom it may be but does it stand the test of modern science?”

I am having trouble embedding this video into my blog, so I have included the link to youtube if you are unable to view this video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2FQfZhO60c

This video explains the practice of Ayurvedic medicine and its applications. The video references that Ayurvedic medicine is not tribal or folk healing, as Western nations would perceive it to be, but that it is a system of medicine on its own. The video gives us insight on how big the business of Ayurvedic medicine is in India and how much people believe in it. It also takes the concept of power and organization in medicine and discusses how Indian authorities regard the system of Ayurvedic medicine. Patient recommendations alone would not be able to convince the medical world, it is the Indian authorities who have the power to make Ayurvedic treatment standardized, and subject it to trials in the same ways as conventional drugs are in biomedicine. Equally important is the videos portrayal of the interplay between Ayurvedic medicine and biomedicine.

I have studied alternative medicine in another anthropology class I have taken, in which we discussed the practice of Ayurvedic medicine. For this class we read a book that introduced the concept of power and organization in medicine. The author states that power in medicine and healing may be compared to other raw materials such as fire, earth, water, and air. They are transformed through domestication, controlled or organized, and exploited for profit, as they are converted into wealth, status, and political power or authority. The author reveals that the “primary resources” of medicine and healing, such as the skills of healers, medicines, and knowledge, have become “secondary resources” as they are researched, certified, institutionalized, commercialized, and constructed by society. To expand our understanding, let’s consider how power in medicine and healing has been controlled, organized, and transformed by society when dealing with Ayurveda.

In the article “Medical Mimesis: Healing Sign of a Cosmopolitan ‘Quack’”, Joan M. Langford discusses how Ayurvedic medicine began to mimic professional biomedicine. The author supports this claim with evidence on the contrast between the “traditional” practice of Ayurvedic medicine and the “new” practice of Ayurvedic medicine. The ancient practice of Ayurveda dealt with human ailments, which continue to affect humans today. Ayurveda, in contemporary times, is trying to adapt to the modernization of humans without losing its observation, intuition, and insight based on ancient philosophy. Current publications make an attempt to convey the relevance of the science of Ayurveda to the need of modern times; however, political and scientific controversies still remain regarding the recognition of Ayurveda in Western nations. Modern medicine is powered by the hegemonic position of biomedicine, which validates a drug or treatment based upon scientific evidence. Furthermore, Western nations appear to have power over determining a drug or treatment’s validation. This hegemony of biomedicine in medical knowledge and practice largely affects the authenticity of Ayurveda. Langford comments on how medical systems are continually modeled after biomedicine with her term of “quackery”, which is “a concept used by medical practitioners and others to discredit medical practices other than biomedicine. Some biomedical doctors consider all Ayurveda to be a kind of quackery, based on a bogus view of the body and dispensing treatment the biological effects of which are scientifically unproven” (25). The power of biomedicine on medical systems is also presented in the article “The Sacred in the Scientific: Ambiguous Practices of Science in Tibetan Medicine” by Vicanne Adams. The author asserts this point by stating, "This assumption in part structures Tibetan views about their own traditions of medicine, often resulting in efforts to make their medicine look and feel the same as what they take to be a uniform and universal ‘Western science’. Others strive to establish the ‘scientific’ natures of things excluded from Western science, in order to establish that their own traditions are equally ‘scientific’" (Adams, 544). Both articles portray this idea that Tibetan medicine and Ayurvedic medicine are based on scientific evidence and principles that may not be understood or validated by Western science or medical practice.

When placed in a different society, alternative medicine, such as Ayurveda, is subject to the hegemonic position of biomedicine, which the practice lacks its scientific justification. Although it remains as the same body of medical knowledge, its treatments and practices are used differently in Western societies and are adapted to fulfill personal needs and desires. As Ayurveda is introduced to a new society, it becomes associated with different discourses and relations of power and control. In addition, as Ayurveda becomes embedded into a different social fabric than that of its country of origin, it becomes perceived differently, and its ideas and practices are adjusted to the new social, political, and economic realms. Thus, Ayurveda loses its recognition of science and authenticity and is incorporated into different hegemonic relations and discourses of power and control.

To understand how or why a particular therapy or practice may be folk at one time or setting, popular in another, and highly professionalized in others, one needs to look at the aspects of rationality in medical tradition. In particular, the aspects of power and organization of medicine need to be addressed. By looking at organization in medicine, one can explore the prevailing patterns within a tradition. There is a need to associate the ideas and practices of medical traditions with the social context in which it was created and practiced. By viewing the social context of health and healing, sectors of health care that determine a practice as folk, professional, or popular, can be adopted to that medical tradition. Although these approaches identify the rationality of a medical tradition, they appear to overlook the economic, political, and ideological foundations that society constructs in health and healing. These influences help to determine which ideas, practices, and traditions will become dominant or marginalized. The roles of medical traditions, like biomedicine and Ayurveda, emerge with the understanding of the coexistence of multiple medical traditions, practices, and thoughts, within cultures and societies.

Works Cited:

Adams, Vicanne. 2001. “The Sacred in the Scientific: Ambiguous Practices of Science in Tibetan Medicine.” Cultural Anthropology 16(4): 542-575.

Janzen, John. Power and Organization in Medicine. 2002.

Langford, Joan M. 1999. “Medical Mimesis: Healing Sign of a Cosmopolitan ‘Quack’.” American Ethnologist 26(1): 24-46.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Creating a "Competent" and "Caring" Doctor

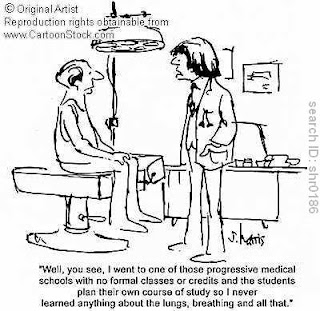

Both images found at: http://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/m/medical_training.asp

Both of the cartoon images above represent the ideas of medical knowledge and training. By providing a glimpse into the practice and curriculum of future physicians, we are surrounded by the idea of creating a “competent” and “caring” doctor, unlike those pictured above. The first image presents the importance of the medical curriculum and how future physicians should or should not be trained. The second image presents the practice of physician and how a physician’s knowledge and training is important in creating a “competent” doctor. In relating these images and both of the articles on “mediating”, I would like to discuss the importance of how medical knowledge is constructed and how the ideologies of health are shaped.

Byron J. Good and Mary-Jo DelVecchio Good’s article “ ‘Learning Medicine’: The Constructing of Medical Knowledge at Harvard Medical School”, studied three groups in the 1990 class at Harvard Medical School, the “New Pathway” curriculum, and the health sciences and technology curriculum. By concentrating on the training of physicians, they believed they could differentiate the “phenomenological dimensions of medical knowledge, on how the medical world, including the objects of the medical gaze—the students and the physicians—are reconstituted in the process, ad how distinctive forms of reasoning about that world are learned” (83-84). The findings of this study are provided in accordance to several themes that encompass medical training, such as:

1. “Medicine is science”. The first two years of the curriculum are emphasized as being science, because medicine is science. Science is factual based and is not affected by or based on value judgments.

2. “The person is the body”. The object of medicine is the individual person, primarily the body.

3. “Medicine is about ‘entering the body’”. Medicine gets inside of the body by case histories and lab exercises.

4. “ ‘Medical gaze’” and its view of the body reconstitute the person as object. In medical training, the student is conditioned to hold the conventional view of the body in a detached manner of seeing the human patient, and to study the view of the person-body.

5. “The ‘medical gaze’ reconstitutes the subject (the student)”. The student has to manage their objective gaze with society’s conventional view of the person-body.

The perspectives of the objective body and the human person, studied by medical students, hold a contradictory message in medical curriculum. The Goods article represents the curriculum as “the dual discourse” of “competence” and “care”. Competence is “associated with the language of the basic sciences, with ‘value-free’ facts and knowledge, skills, techniques, and ‘doing’ or action’” (Good, 91). This part of medicine is given priority because it is presumed as the basis of medical practice. Caring is “expressed in the language of values, of relationships, attitudes, compassion, and empathy, the nontechnical or as one student called it the ‘personal’ aspects of medicine” (Good, 91). This dual discourse creates a progression of dichotomies surrounding the qualities and problems of medical education on how to create “caring” and “competent” physicians.

In the article “Against Global Health? Arbitrating Science, Non-Science, and Nonsense through Health”, the author Vicanne Adams offers a “critical exploration of the processes by which the notion of ‘health’ in Global Health Sciences holds a tyrannical relationships to problems within the actual practices of global health” (40). The author argues that the conversations of “health” between doctors, patients, and politicians are not all talking about the same thing, in which the recognition of “health” is culturally constructed and socially sustained. The author gives us insight on the boundary between “science” and non-science”. In addition, the author discusses the debate on health in two ways. First, the author presents the cultural meanings of health and examines the ideologies that construct its meaning. Second, the author presents approaches in how to move forward, and to discover the principles behind “health”, in order to produce healthier interactions about our bodies.

In both articles we are presented with the notion that the study of medical knowledge and education is a comparative perspective. Physicians are an important source of information on how to achieve health and/or well-being. The roles of physicians need to be taken more persistently with a sense of humanity and a better eye for examining the patient holistically. I believe there needs to be a new message advocated by medical schools to physicians that goes beyond treating just the body, but takes a more holistic approach in diagnosing and treating a patient. The reason physicians should change how they view and diagnose a patient stems from the perspective that treating the body leaves out social, political, and economic variables of health. In order to create “competent” and “caring” physicians, the argument then is to start this paradigm shift of thinking in physicians when they are in medical school by changing the way physicians are educated to cure or improve a person’s health. The solution for physicians to balance out the needs of the physical body and the human person perspective of patients is to implement global health education on determinants of health and disease into medical school curriculums. Global health is important to medical knowledge and education because the demographic of patients is ever changing, multi-cultural, and diverse in many other ways. The world has become progressively more interconnected by the determinants of health and disease, including socioeconomic, environmental, and political factors, and globalization now affects almost everyone’s lives. An increase in the flow of people, goods, services, and information between countries has a powerful influence on the world’s health and health care. The global migration of people and products increases the threat of disease and highlights the connections in health and medicine. Today, the emergence of a new public health threat to individuals in one area of the world becomes a threat to all individuals throughout the world. Teaching the global aspects of medicine and understanding medical resources and care in a developing country will prepare physicians and give them a better understanding of health and medicine. In turn, this will make for better physicians and strengthen the health care system. In summary, newly trained physicians need to be well rounded on global health issues, understand emerging global diseases, and be cross-culturally sensitive, in order for medical schools to educate and create “competent” and “caring” physicians.

Sources:

Adams, Vicanne. “Against Global Health? Arbitrating Science, Non-science, and Nonsense through Health.” Against Health: How Health Became the New Morality. New York: University Press, 2010.

Good, Byron and Mary-Jo. Learning Medicine: The Constructing of medical Knowledge at Harvard Medical School. Knowledge, Power, and Practice. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Friday, January 14, 2011

Controversy Over Invasive Prenatal Testing: The Up Side of Down's

Description: "In Australia, there is more freedom to abort and here is a controversy that has arisen that to me seems amazing. People sueing for damages when found there child was born with down syndrome and they weren't given this information so they could abort their child. Is it really about love? Or is it about greed?"

http://community.heywhateversocial.info/_Abortion-and-information-on-reasons-to-abort/VIDEO/1178891/22914.html

The subject of prenatal testing for Down syndrome is an emotionally charged one. The Frontline video provides us with an array of examples of the advantages and disadvantages of prenatal screening and testing, particularly pertaining to screening for Down Syndrome by amniocentesis. The first example provided is about a couple who underwent screening and ending up keeping their baby, despite the positive diagnosis that their baby had Down Syndrome. The second example is about a couple who is not given the chance to undergo screening for Down Syndrome, in which they are told that the test was not available, and the couple ends up suing the hospital for not providing the opportunity to screen for abnormal defects or disease of the fetus . Lastly, the third example is about a couple who also sues the hospital for not allowing amniocentesis to be done, after tests by the ultrasound had detected problems with the pregnancy and abnormalities of the fetus. All of these examples exemplify the controversies surrounding blood tests, ultrasounds, and invasive screening during pregnancy. The comment in the video, “All patients are not equal when testing for Down Syndrome”, is illustrated by all three of these examples, as each provides an example of how the different couples are treated when undergoing prenatal testing. The video ends with a proposal to this problem and controversy about prenatal testing by concluding that the problem should not have to do with the increased costs of raising a child with special needs, but the problem is about fixing the support system for these families, rather than individual litigation.

Rayna Rapp’s article “Accounting for Amniocentesis”, focuses on difficult decision making of pregnant women who are counseled to undergo amniocentesis to detect genetic abnormalities in their fetuses, mainly the abnormalities pertaining to Down Syndrome. The article provides an analysis of the moral complexities and social impacts of amniocentesis. Rapp is particularly considerate of the ways the prenatal testing technologies become signifiers of “scientific literacy” and social status. The article centers around the genetic counseling and testing centers that deal with patients of different social strata and ethnic backgrounds, which allows for economic and cultural comparisons among heterogeneous patients that approach prenatal testing with a range of social, moral, and political beliefs and concerns. Rapp’s article provides a personal look at the differences among the reproduction of and the cultural apprehension among amniocentesis, based upon how moralities figure into women’s testing decisions and understandings.

In comparison, the Frontline video conveys some of the implications made in Rapp’s article on the “social impact and cultural meaning of prenatal diagnosis” (Rapp, 70). Drawing upon amniocentesis stories, Rapp “raises the problem of how to understand the development and routinaization of prenatal diagnosis” (55). The problem is most often found as “combining the literature on “patient reactions to prenatal diagnosis”, which is highlighted in the video as the reactions of the couples and their concerns are uncovered according to parental screening and diagnosis (60). Rapp furthers our understanding of the problem in her efforts of finding “four overlapping medical discourses: geneticists spoke of the benefits and burdens their evolving technical knowledge conferred on patients; heath economists deployed their famous cost/benefit analysis to suggest which diseases and patient populations should be most effectively screened; social workers and sociologists interrogated the psychological stability and decision-making strategies of “couples” faced with “reproductive choices”; and bioethicists commented on the legal, ethical, and social implications of practices in the field of human genetics” (60). Both the video and Rapp’s article illustrate the particular interest and controversy of childbirth experiences and how birth has become more medicalized through time, including the events that lead up to birth, the practices surrounding birth, the techniques and technological tools utilized by traditional and biomedical practitioners, and the differences in practice across cultures.

Amniocentesis has become a controversial topic of expecting parents due to its advantages and disadvantages and ethics. I would like to expand on the social impacts and cultural meaning of prenatal diagnosis portrayed in both the video and the article by discussing the pros and cons of the test of amniocentesis. The pros and cons of this controversial prenatal test continue to increase with time. After reviewing the pros and cons of this test that is used to determine whether a baby has a genetic or chromosomal defect, I believe it should be offered to pregnant women who want to have it, and here’s why: amniocentesis offers many advantages to the expecting mother (and father). Amniocentesis identifies genetic disorders, one of the most common being Down Syndrome, in which identification of theses disorders can determine whether the baby is at risk to various conditions and check the well-being of the baby. It is important to determine whether the baby is maturing correctly and developing properly to ensure the baby’s and mother’s safety during pregnancy and labor. By undergoing amniocentesis, women who have babies that are diagnosed with an abnormality, or one of the diseases, can gain advanced knowledge of the special needs that the child may need, and better prepare before the birth of their child to accommodate these particular needs. This would allow the parents to seek better care for their child and find hospital’s specializing in these needs, so that parents are better equipped for the birth of their child. This test is important, as it provides the mother with information about her baby. Amniocentesis also offers various disadvantages, aside from the many advantages, however. The test runs the risk of miscarriage and/or infection, in which each of these risks should be considered before having the test done. In addition to the health risks, this test has become a controversial issue because of ethical perspectives. For women who receive the results that their baby has a defect, these women can choose to raise their child or have an abortion, which raises the ethical question about the use of the test. For those who choose to abort are making their own choice, however many view this as unethical. After weighing these advantages and disadvantages of amniocentesis, I believe it is up to the mother to decide if she would like the test. I personally believe that the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. Lastly, I would like to note that almost all tests done in hospitals exist with either medical risks or ethical controversy, and amniocentesis is one of these critical issues. However, through the use of amniocentesis, this test can provide an advance in technology and science for generations to come, and researchers can one day discover ways of treating these defects found, in order to help future parents who experience the birth of a child with a defect.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)