Currently in the United States, the human body defines a profitable site of “reusable” parts, which range from whole organs down to microscopic tissues. Although the medical practices that facilitate the transfer of parts from one human body to another reduce suffering and extend lives, these practices have also altered perceptions of the values assigned to the body. The practices shaping American biomedicine are seen as pervasive, and sometimes destructive, compelling scientific inquiry and social critique.

http://www.king5.com/news/Death-row-inmate-wants-to-donate-organs-117762369.html

This video (and the related article) raises ethical, legal, medical, and social issues. Should “one of Oregon’s most notorious killers” be allowed to end appeals to his death sentence in order to donate his organs? Christian Longo, the “notorious killer”, thinks so, he wants to alter his protocol for lethal injection to fulfill his wish. Longo was convicted of killing his wife and three children in 2003, in which he stated he did so “in order to live an uninhibited lifestyle”. Longo’s issue to donate his organs was recently brought to recent news with submission of his Op-Ed piece, “Giving Life After Death Row”, in the New York Times. Longo writes, “I spend 22 hours a day locked in a 6 foot by 8 foot box on Oregon’s death row. There is no way to atone for my crimes, but I believe that a profound benefit to society can come from my circumstances. I have asked to end my remaining appeals, and then donate my organs after my execution to those who need them. But my request has been rejected by the prison authorities”. In addition to Longo admitting his guilt, he has founded a group called “Gifts of Anatomical Value From Everyone, or G.A.V.E.”. This is an organization set up to “make a difference in the organ shortage in the U.S. with the help of willing and healthy volunteer prisoners. Prisoners frequently ask to help whether through living kidney donations or multiple donations after execution to anyone in need. But they are just as frequently denied unnecessarily by prison administration and transplant authorities”. In his Op-Ed piece, Longo argues, “According to the United Network for Organ Sharing, there are more than 110,000 Americans on organ waiting lists. Around 19 of them die each day. There are more than 3,000 prisoners on death row in the United States, and just one inmate could save up to eight lives by donating a healthy heart, lungs, kidneys, liver and other transplantable tissues”. Furthermore, Longo claims, “If I donated all of my organs today, I could clear nearly 1 percent of my state’s organ waiting list. I am 37 years old and healthy; throwing my organs away after I am executed is nothing but a waste”. The current procedure for those on death row in Oregon, along with other states, requires death by three lethal drugs injected, which destruct organs and make them unfit for transplants. In the video, Longo suggests an appeal to switch to one lethal drug that would kill him, and simultaneously allow his organs to be saved and donated. However, the state has denied his request, claiming his requests to change his death row appeal and change the lethal injection protocol are mutually exclusive. His requests raise many issues of concern, such as logistical and health concerns. A common concern involves the prevalence of disease, such as increased rates of H.I.V. and hepatitis in the prison population, which can effect the prisoner’s organs. However, tests can be administered to determine whether the prisoner’s organs are healthy. Another concern is on fears about security; the donation of organs by prisoners can be seen as an “elaborate escape scheme”. However, it is argued that prisoners do receive other medical care at outside hospitals and are executed on prison grounds, meaning that donating does not produce the risk of escape. Additionally, there is public apprehension towards prisoners donating organs due to the previously publicized case of “Gov. Haley Barbour of Mississippi released two sisters who had been sentenced to life in prison”. By donating organs, in this previous case, a kidney of one sister to the other, provides an expectation that prisoners can receive privileges and reductions in their sentences, and might be given the option to leave prison alive. Lastly, there is the concern of abuse. The acceptance of voluntary donations provides the opportunity to abuse these choices, which has been demonstrated by past history of medical experiments on prison inmates. However, it is argued that prisoners should be allowed to initiate a request to donate their organs without any “enticements”. Longo claims that many other men on death row express the wish to donate their organs, as well. Does the public, especially those in need of organ transplants, disagree with the prison authority’s response in denying Longo’s request? Or do they express the many concerns surrounding organ donations by prisoners? Who is to decide if a prisoner on death row can or cannot donate their organs?

Organs are rapidly becoming commodities, in which American attitudes towards life and death are modified. In the article, “Aged bodies and kinship matters: The ethical field of kidney transplant”, the authors discuss how modern medicine defines “death within a framework of ethical decision making that emphasizes the fight against specific moral diseases and conditions” (Kaufman et al. 81).The authors argue that the ultimate decision of morality is "a sacrifice of the wholeness of the body and a nonreciprocal bargain”, in which “the possibility of receiving the body part of another- the always already quality of this social fact- becomes part of the calculus by which the potential risk to another life and the sacrifice of another’s bodily integrity are weighed in relation to the value of extending one’s own life and improving one’s own well being” (Kaufman et al. 83-85). As a result, “the availability of interventions as therapeutic possibilities elicits hopes for and expectations of cure, restoration, enhancement and improved quality of life” (Kaufman et al. 83). The article discusses how effective procedures “become routine and thus expected and desired by clinicians, patients, and families”, additionally, ”when techniques become less invasive and associated with lower mortality risk, consumer demand for them and ethical pressure to make them available both increase" (Kaufman et al. 82). As time has evolved, new ways of seeing medicine have been established, as the authors state, “Just as the sonogram opened ways of seeing the fetus, its malformations, and the idea of pre-birth intervention, just as surrogacy opened up the idea of motherhood and family, and just as cardiac surgery, the mechanical ventilator, and emergency CPR changed ways of thinking about the risk of death, so, too, the idea of organs moving from children to parents, between spouses, or between friends or strangers opens up the old issue of social and familial obligation to emerging biotechnical means of expression”(Kaufman et al. 95). Medical and technological advances, in particular organ donation, have created new alternatives to defeating death and viewing life, which in turn, have produced ethical and moral issues concerning obligation and choice.

Nancy Scheper-Hughes' article, “The Last Commodity: Post-Human Ethics and the Global Traffic in ‘Fresh’ Organs”, discusses the ethics of organ transplants and the “moral and ethical gray zone- the lengths to which it is permissible to go in the interests of saving or prolonging one’s own life at the expense of diminishing another person’s life or sacrificing the cherished cultural and political values” (147). Our sense of “body holism, integrity, and human dignity” are restricted by “free market medicine” which “requires a divisible body with detachable and demystified organs seen as simple materials for medical consumption” (Scheper-Hughes 155). Additionally, “the transformation of a person into a life that must be prolonged or saved at any cost has made life into the ultimate commodity fetish. The belief in the absolute value of a single human life saved or prolonged at any cost ends all ethical inquiry and erases any possibility of a global social ethic” (Scheper-Hughes 158). As these medical transactions take place “from black and brown bodies to white ones, and from females to males”, there is “little empathy for the donors, living and brain dead. Their suffering is hidden from the general public. Few organ recipients know anything about the impact of the transplant procedure on the donor’s body” (Scheper-Hughes 150,161). “Social kinship” produced by the supply of organs is created to “link strangers, even at times political enemies from distant locations who are described by the operating surgeons as 'a perfect match--like brothers'” (Scheper-Hughes 150). The obligation to prolong and save the life of another person outweighs the medical risks of surgery or later impacts that may affect the donor’s life later on. It has become a choice to become an organ donor and help save the lives of others, thus moral and ethical issues accompany the choices and/or obligations of organ transplant patients and organ donors.

Our limitations concerning the notions of life and death have changed with the advancement of medicine and technology. Our values of the body are modified through time, as health becomes one of the main concerns of our society. We have become bounded within the framework of biomedicine and the surrounding issues of choice as one seeks to defer death and prolong life. Such ethical and moral concerns concerning organ transplants promote the progress and promise of extending human life. Has the hope to maximize human life extended far beyond what nature has intended? Medicine, science, and technology have already increased the human life span, so what’s next?

Sources:

Sharon R. Kaufman, Ann J. Russ, and Janet K. Shim. 2006. “Aged Bodies and Kinship Matters: The Ethical Field of Kidney Transplant.” American Ethnologist 33(1): 81-99.

Nancy Scheper-Hughes. 2005. “The Last Commodity: Post-Human Ethics and the Global Traffic in ‘Fresh’ Organs.” Pp. 145-167. In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/06/opinion/06longo.html?_r=1&scp=1&sq=%22christian%20longo%22&st=cse?kgw

http://www.gavelife.org/

Thursday, March 10, 2011

Friday, March 4, 2011

The Meaning of Life and Death

While death is a natural event, meaning that cells die and body systems fail, our experiences with death continue to be shaped and influenced by medical and cultural practices and trends. We are surrounded with many questions concerning the “meaning” of death, as our experiences and perceptions of death include many issues of morality. With more of us living longer and dying from chronic conditions rather than acute diseases, new medical technologies have been created to prolong life. Dying bodies are kept alive with medications and machines; however, these technologies raise questions about the quality of life and challenges are made against these life-prolonging measures. While the traditional view of death is seen as the “enemy”, systems have been created in order to “defeat” death and make it less “feared”, such as organ “harvesting” and transplantation. To make the process of dying easier and more comfortable, we have institutionalized hospice and palliative care. Through time, death has become a process that is less hidden, talked about, and individualized.

In my Comparative Study of Death class, we have talked about the differences between dying, (being) dead, and death. All three are connected with the experience of death, where death is defined as a process, (being) dead is defined a condition or state that the body is in, and lastly, death is defined as the transition from being alive to being dead and is what intervenes between dying and (being) dead. Our experiences of death are seen as a process and end as a state. “Acceptance” or “denial” of death depends on a variety of factors—social, circumstances of the case, cultural responses, and individual needs. Kubler-Ross wrote about the stages of death: denial and isolation, resentment and anger, bargaining, depression and hopelessness, and acceptance. In addition, each person will travel through these stages in their own way.

This YouTube video is a dark satire portraying our conceptions of what death really is and what it means to us as individuals. Once death arrives, decisions are made, and the choices vary. Contrary to our American dominant ideologies, the video portrays death as an event, rather than a process. The people in the video come to terms with death, and come up with strategies to defend themselves from death. Their fluctuating reactions project what Kubler-Rose describes as the stages of death. The individuals go from denial to acceptance, which all the stages are expressed through their reactions. When they are told they are dead by the grim reaper, they feel an experiential blank, where the phenomenon of anticipatory grief has occurred because they have been forewarned. In addition to these reactions, the video brings up the issue of what awaits for the newly deceased. Conceptions of the afterlife question what souls are, where they reside within us, and where do they go once we are dead. At the end of one’s life, feelings are evoked out of loss of agency in the world and moral personhood. The subjectivity of the body becomes objectified. All of these issues are open to question and subject to personal beliefs. Despite spirituality and achievement of a meaningful death that is “dignified”, death can be painful, full of contradictions, and fearful.

For a majority, the representation of factors such as cultural practices or rituals, religious beliefs or ideation, societal norms or laws, deeply influence individual choices and medical concerns. Margaret Lock’s article, “Living Cadavers and the Calculation of Death” discusses aging, dying, and the difference between health care systems and cultures. Lock states, “In North America, a brain dead body is biologically alive in the minds of those who work closely with it, but is no longer a person, whereas in Japan…such an entity is both living and remains a person, at least for several days after the brain death has been diagnosed” (150). The article examines intensive care units (ICU) and the use of medical technology, such as artificial ventilators. The use of these apparatus’ is created for human entities whose brains are diagnosed as irreversibly damaged, but whose bodies are kept alive by technological support. Lock describes “brain dead” patients as “betwixt and between, both alive and dead, breathing with technological assistance but irreversibly unconscious” (136). There is a gray area between what is considered alive and what is considered dead. Amongst these ailments, the management of dying people is what palliative medicine and care are for. In addition, Lock discusses the value of such brain-dead bodies, as they provide potential value towards the supply of donors for human organs to transplant. This dominant ideology is widely disputed and has different effects across cultures. Furthermore, Eric L. Krakauer’s article, “To Be Freed from the Infirmity of (the) Age”, also discusses the use of medical technology and its quest to control death. The use of medicine and technology can be used to free us of our “infirmity of age”. Krakauer states, “Deferring death becomes more important than attending to the soul or preparation for the afterlife or the next” (390). This reflects the dilemma between the conflicting values of medicine and morals and gives insight on bioethical concerns. By affirming one’s goals at life’s end, a person can die a “dignified death”. Additionally, in the midst of suffering at the end of one’s life, comfort and meaning can be provided. These articles allow us to rethink a medical death in larger, more humanistic terms.

In order to consider the meaning of death, we must look at the meaning of life and the relationship between life and death. One may believe that where there is life there is hope. Through the stories of suffering, hope begins with the decision to survive. The metaphorical “fight” against illness is taking on all of life’s aspects, for better or for worse. Life is not only about surviving, it is about engaging in the life we have and embracing it. It is one thing to be alive physically, it is another thing to be alive emotionally and spiritually. James W. Green’s book, “Beyond the Good Death”, examines the ways in which Americans react to death not only for themselves, but also, for those they care about. On the back of the book, Green states, “A compassionate physician once remarked that in his neonatal intensive care unit ‘no one dies in pain and no one dies alone.’ That was his policy: humane, honest, straightforward. But it is not that simple, as he knew. Like birth and marriage, death is ritually dense in all cultures, creating occasions when belief and ritual are as present and as important as the physician’s ministrations. In no society do people simply leave the dead as they are and unceremoniously walk away…Despite the routine disclaimers on death certificates, no on dies a ‘natural death.’ As culture-baring primates we do not have that option”. Each person, each culture is complex, as well as the experiences and practices surrounding death. If one can have a “lifestyle”, can one have a “deathstyle” too?

Sources:

Green, James W. 2008. “Beyond the Good Death: The Anthropology of Modern Dying”. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Krakauer, Eric L. 2007. “To Be Freed from the Infirmity of (the) Age: Subjectivity, Life-Sustaining Treatment, and Palliative Medicine.” In Subjectivity: Ethnographic Investigations. Joao Biehl, Byron Good, and Arthur Kleinman, eds. Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 381-397.

Lock, Margaret. 2004. “Living Cadavers and the Calculation of Death”. Body and Society 10(2-3): 135-152.

In my Comparative Study of Death class, we have talked about the differences between dying, (being) dead, and death. All three are connected with the experience of death, where death is defined as a process, (being) dead is defined a condition or state that the body is in, and lastly, death is defined as the transition from being alive to being dead and is what intervenes between dying and (being) dead. Our experiences of death are seen as a process and end as a state. “Acceptance” or “denial” of death depends on a variety of factors—social, circumstances of the case, cultural responses, and individual needs. Kubler-Ross wrote about the stages of death: denial and isolation, resentment and anger, bargaining, depression and hopelessness, and acceptance. In addition, each person will travel through these stages in their own way.

This YouTube video is a dark satire portraying our conceptions of what death really is and what it means to us as individuals. Once death arrives, decisions are made, and the choices vary. Contrary to our American dominant ideologies, the video portrays death as an event, rather than a process. The people in the video come to terms with death, and come up with strategies to defend themselves from death. Their fluctuating reactions project what Kubler-Rose describes as the stages of death. The individuals go from denial to acceptance, which all the stages are expressed through their reactions. When they are told they are dead by the grim reaper, they feel an experiential blank, where the phenomenon of anticipatory grief has occurred because they have been forewarned. In addition to these reactions, the video brings up the issue of what awaits for the newly deceased. Conceptions of the afterlife question what souls are, where they reside within us, and where do they go once we are dead. At the end of one’s life, feelings are evoked out of loss of agency in the world and moral personhood. The subjectivity of the body becomes objectified. All of these issues are open to question and subject to personal beliefs. Despite spirituality and achievement of a meaningful death that is “dignified”, death can be painful, full of contradictions, and fearful.

For a majority, the representation of factors such as cultural practices or rituals, religious beliefs or ideation, societal norms or laws, deeply influence individual choices and medical concerns. Margaret Lock’s article, “Living Cadavers and the Calculation of Death” discusses aging, dying, and the difference between health care systems and cultures. Lock states, “In North America, a brain dead body is biologically alive in the minds of those who work closely with it, but is no longer a person, whereas in Japan…such an entity is both living and remains a person, at least for several days after the brain death has been diagnosed” (150). The article examines intensive care units (ICU) and the use of medical technology, such as artificial ventilators. The use of these apparatus’ is created for human entities whose brains are diagnosed as irreversibly damaged, but whose bodies are kept alive by technological support. Lock describes “brain dead” patients as “betwixt and between, both alive and dead, breathing with technological assistance but irreversibly unconscious” (136). There is a gray area between what is considered alive and what is considered dead. Amongst these ailments, the management of dying people is what palliative medicine and care are for. In addition, Lock discusses the value of such brain-dead bodies, as they provide potential value towards the supply of donors for human organs to transplant. This dominant ideology is widely disputed and has different effects across cultures. Furthermore, Eric L. Krakauer’s article, “To Be Freed from the Infirmity of (the) Age”, also discusses the use of medical technology and its quest to control death. The use of medicine and technology can be used to free us of our “infirmity of age”. Krakauer states, “Deferring death becomes more important than attending to the soul or preparation for the afterlife or the next” (390). This reflects the dilemma between the conflicting values of medicine and morals and gives insight on bioethical concerns. By affirming one’s goals at life’s end, a person can die a “dignified death”. Additionally, in the midst of suffering at the end of one’s life, comfort and meaning can be provided. These articles allow us to rethink a medical death in larger, more humanistic terms.

In order to consider the meaning of death, we must look at the meaning of life and the relationship between life and death. One may believe that where there is life there is hope. Through the stories of suffering, hope begins with the decision to survive. The metaphorical “fight” against illness is taking on all of life’s aspects, for better or for worse. Life is not only about surviving, it is about engaging in the life we have and embracing it. It is one thing to be alive physically, it is another thing to be alive emotionally and spiritually. James W. Green’s book, “Beyond the Good Death”, examines the ways in which Americans react to death not only for themselves, but also, for those they care about. On the back of the book, Green states, “A compassionate physician once remarked that in his neonatal intensive care unit ‘no one dies in pain and no one dies alone.’ That was his policy: humane, honest, straightforward. But it is not that simple, as he knew. Like birth and marriage, death is ritually dense in all cultures, creating occasions when belief and ritual are as present and as important as the physician’s ministrations. In no society do people simply leave the dead as they are and unceremoniously walk away…Despite the routine disclaimers on death certificates, no on dies a ‘natural death.’ As culture-baring primates we do not have that option”. Each person, each culture is complex, as well as the experiences and practices surrounding death. If one can have a “lifestyle”, can one have a “deathstyle” too?

Sources:

Green, James W. 2008. “Beyond the Good Death: The Anthropology of Modern Dying”. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Krakauer, Eric L. 2007. “To Be Freed from the Infirmity of (the) Age: Subjectivity, Life-Sustaining Treatment, and Palliative Medicine.” In Subjectivity: Ethnographic Investigations. Joao Biehl, Byron Good, and Arthur Kleinman, eds. Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 381-397.

Lock, Margaret. 2004. “Living Cadavers and the Calculation of Death”. Body and Society 10(2-3): 135-152.

Thursday, February 24, 2011

Defining ‘Normal’

http://static.howstuffworks.com/gif/define-normal-1.jpg

How do you tell if you're in the box or out of it?

Most of us spend some portion of our lives pondering if we’re “normal”. Is being “normal” in the box or out of it? The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) estimates that more than 1 in 4 Americans have a mental disorder. Most people consider someone with a mental disorder to have behaviors, feelings, and thoughts that deviate from the norm. Someone who is not considered “normal” does not “fit in” with what is socially and medically deemed “standard”. When we contemplate what it really means to be “normal”, we often associate what is “normal” with whether the way we think or act is the same or similar to the majority of other people and society. When we evaluate our own behaviors, we decide how to act based on the established parameters of what is considered acceptable, or normal, social behavior. To many, normal means average or standard. In addition, social standards strongly influence the idea of what is “normal”. By examining society’s laws of what is culturally considered “normal”, we are left with many questions on how these perceptions came about. Who defines what is “normal” and what is not? How do we construct what is in the box and what is out? As seen through the eye of the beholder, what is considered “normal” is filtered through the lens of society.

Here is a link to a video:

http://videos.howstuffworks.com/tlc/28826-understanding-genes-and-human-behavior-video.htm

Understanding: Genes and Human Behavior

“On the Learning Channel series "Understanding: The Power of Genes", researchers try to find the link between genes and human behavior”.

This video succinctly discusses the complex relationship between genes and human behavior. The video claims that “genes may predispose us to act certain ways, even when it comes to such things as taking risks”. The actions of jumping off the high-dive into the pool and/or deciding to walk back down the stairs and stay on ground are, according to the video, the “character traits in genes we inherit”. The video addresses two contrasting behaviors that are correlated with the “novelty seeking gene” and the “anxiety gene”. The “novelty seeking gene makes his (or her) brain respond to dopamine” and it is “released in a positive way”. The “anxiety gene controls serotonin” and “makes his (or her) brain feel bad, anxious, worried”. As seen in the video, individuals who possess either of these genes tend to behave in two very different ways. What is felt as novel, or exciting, for one person, may make another person feel anxious or terrified. Are both behaviors considered to be “normal”? Or is one to be considered a more acceptable social behavior?

The articles by Rose, Talbot, and Elliott, speak to the issue of over-medicalization of behaviors that are not considered “normal”. In the book, “Better Than Well”, by Carl Elliott, the chapter, “The Face Behind the Mask”, refers to America’s love-hate relationship with what Elliot calls ‘enhancement technologies’ that is present in our society. The author claims that before the 20th century, Americans classified people by their character, and in the early 20th century, people were classified by their personality. Elliott states that character was “about the depths beneath the surface, about what is on the inside as well as what other people see”, and personality was about “the idea of self presentation” (60). In turn, “Americans started to take on the idea that we all put on a mask for the world. Everyone is a performer” (Elliot, 60). The goal was to be “socially successful”, in which “not only do we have to behave in certain ways, we have to be certain ways as well” (Elliot, 60). In addition, the author addresses the medicalization of the personality trait of shyness. The medicalization of shyness lead to it’s diagnosis in the DSM as a mental disorder, first categorized as a “social phobia”, and then the term “social anxiety disorder” was created. To help “cure” these disorders, Paxil was advertised as the drug of choice. Within the last century, there has been an explosive response to these disorders and prescribing drugs such as Prozac, Zoloft, and Cymbalta. Those who benefit most from the diagnosis of “mental disorders” are the pharmaceutical companies. These companies are gaining profit by giving out the “magical pill” that will cure your “disorder”. The pharmaceutical companies begin to overtake scientific studies and results and become dependent to mental disorders by selling these “illnesses” through advertisement and persuade society to purchase these pills as a result of self and misdiagnosis.

Has this become the “norm” of our society?

http://www.joe-ks.com/archives_jun2008/PillMan.jpg

The above image represents society’s current obsession with treating behaviors that are not considered “normal” with pills. Pills are constantly being created and taken for everything. Has our society become dependent on pills that claim to “cure all”? Pharmaceutical companies have created various assortments of drugs to treat different conditions that science, and we as a culture, have come to medicalize. In addition, pharmaceutical companies spend millions each year on the advertisement of these drugs to be represented in the media. These constant reminders surround our everyday lives and send the message that you could possibly be suffering from one of these disorders and need a certain pill to “fix it”.

Nikolas Rose’s article, “Neurochemical Selves”, refers to the relationship between drugs and behaviors by arguing that “drugs do not so much seek to normalize a deviant but to correct anomalies, to adjust the individual and restore his or her capacity to enter the circuits of everyday life” (210). In addition, Rose states, “While our desires, moods, and discontents might previously have been mapped onto a psychological space, they are now mapped upon the body itself, or one particular organ of the body—the brain. And this brain is itself understood in a particular register. In significant ways, I suggest, we have become “neurochemical selves” (188). The phenomenon of neurochemical selves is deeply embedded in the process of modifying the abilities in our life’s work to become “active” citizens, devoid of “anomalies”. Rose states, “In the eugenic age, mental disorders were pathologies, a drain on a national economy. Today, they are vital opportunities for the creation of private profit and national economic growth” (209). This suggests that people and their mental disorders can be considered as a means for “profit” and “economic growth”, which reiterates the obsession with diagnosing mental disorders and the creation of drugs as treatment for these disorders.

Doctors have begun to over-prescribe drugs and over-diagnose disorders, which has lead to the problem of prescription drug abuse. The article, “Brain Gain”, by Margaret Talbot, discusses the over-medicalization of “disorders” and over-prescription of drugs to treat them. This pushes peoples desire to “perform” even better, to be considered “normal” and a pill is needed in order to compete in this vicious cycle. The article describes students’ desires to boost cognitive functions, in which, “People in her position could strive to get regular exercise and plenty of intellectual stimulation, both of which have been shown to help maintain cognitive function. But maybe they’re already doing so and want a bigger mental rev-up, or maybe they want something easier than sweaty workouts and Russian novels: a pill”(4). This represents our society’s desire towards improving ourselves and “taking the easy way out”. In western society, we have created a society based on the norms of getting things done fast and right, in order to get ahead in life. Talbot states, “Every era, it seems, has its own defining drug. Neuroenhancers are perfectly suited for the anxiety of white-collar competition in a floundering economy” (11). Many of us have become dependent on these neuroenhancing drugs to help us get ahead and succeed in life; these drugs have become “normal” to our society. These drugs are enabled by pharmaceutical companies and doctors who prescribe them. Should our society sit back and let drugs overrule our lives? Why can’t we be happy with who we really are? What really is “normal”?

Sources:

Elliot, Carl. 2003. “The Face Behind the Mask” and “Amputees by Choice.” In Better Than Well: American Medicine Meets the American Dream. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. Pp. 54-76, 208-236.

Rose, Nikolas. 2007. “Neurochemical Selves.” In The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Pp. 187-223.

Talbot, Margaret, “Brain Gain: The Underground World of ‘Neuroenhancing’ Drugs.” The New Yorker, April 27, 2009.

Thursday, February 17, 2011

Modern Health and Disease

Dieting has become deeply integrated into the American culture. Many people in the U.S. are on a diet in one way or another, whether it is counting calories or checking waistlines. Diet names such as “Weight Watchers”, “Atkins Diet”, and “South Beach Diet” become familiar to our every day language and are recognized because we begin to hear them all the time. One modern approach to an ancient way of eating is the “Paleo Diet”.

http://www.crossfittheclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/paleo_diet_caveman_poster-p228497097265485886t5ta_400.jpg

The “Paleo Diet” is considered to be a way of eating, rather than dieting, and dates back to ancient times, before many of us existed. This diet is based upon the types and quantities of foods that hunter-gatherers once ate. This diet consists of lean meat, seafood, fruits and vegetables. The “Paleo Diet”, which has been adapted through evolution and natural selection, imitates the diet of our hunter-gatherer ancestors—a diet high in protein, fruit, and vegetables, with moderate amounts of fat and high quantities of omega-3 and monounsaturated fats. By modifying our modern ways of dieting to be adjacent with our ancestors’ ways of eating seems to provide health benefits.

In the article “Globalizing the Chronicities of Modernity”, Dennis Wiedman reflects on the responses to the chronicities of modernity. Wiedman portrays the major changes in health by stating, “For most of human history as hunters, gatherers, and agriculturalists, humans maintained an active physical lifestyle that varied with seasonal resources and promoted cardiovascular and metabolic fitness. But for the past five hundred years, since early European imperialism, there have been major changes in everyday life and, in consequence, in health” (38). The author addresses the concept of chronicity, an idea used to explain individual and local ways of life, question public health discourse, and consider the relationship between health and the globalizing forces that influence and/or shape it. Wiedman’s main argument is the “theory of chronicity”, which is developed to “reconceptualize and explain the global pandemic of MetS, by arguing that its underlying cause is the dramatic shift from ‘seasonality’ of hunters, gatherers, and agriculturalists to the ‘chronicities of modernity’” (38). With modernity, we see more results of chronic conditions. Wiedman discusses the association of diabetes with the metabolic syndrome (MetS), and how these chronic conditions have become increasingly prevalent in developed and developing nations. The article documents the effects of modernity by “reflecting the rapidity of the demographic and cultural transition” and how it “portrays the critical juncture of modernity as populations transition from subsistence agriculture to a cash economy, from self-produced foods to store-bought foods, from vigorous household chores to the comforts of household appliances, and from actively walking to riding in cars and trucks” (Wiedman, 42). Contemporary examples of modern lifestyles display the connection between the chronicities of modernity and the increased prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes and MetS. Wiedman’s article also discusses the health consequences in relation to globalization. Wiedman describes globalization as the “intensification of worldwide social relations”, in which “production, distribution, transportation, communication, and financial systems link the local to the global” (45). The “aspects of globalization”, in which individuals interactions and social structures become “more uniform”, are said to “jeopardize health” (Wiedman, 45-46). This article explores the unequal impact of chronic illness and disability on individuals, families, and communities in diverse local and global settings.

Here is a link to a video by Dr. Oz on “The Healthiest Diets”:

http://videos.howstuffworks.com/sharecare-videos.htm

This video looks at diets from around the world, why they work, and how to bring them to your own lives and home. Dr. Oz was featured as the “health expert” on the “Oprah Winfrey Show”. In this video, Dr. Oz proposes that certain countries, which diets consist mainly of whole-grain and legumes like beans and rice, in addition to fruits and vegetables, have the best health. The combination of whole, natural foods found among other countries diets, are suggested to provide better nutrition and lower rates of heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

Food practices vary from country to country. There are obvious social, cultural, political, and economic factors that influence our perspectives on health and disease. The article “Chronic Conditions, Health, and Well-Being in Global Contexts” , claims that approaches to health should provide “a more powerful appreciation of context—that is, how environments are shaped by physical, geographical, social, cultural, political, ethno-racial, gender, economic, and class-based systems of enablement and oppression” (238). If we take a critical standpoint and look at these multidimensional factors of social, economic, and political conditions that influence and affect health, we are able to understand these conditions and improve the lives of people with chronic conditions. The ideologies of health and disease have affected the relationship between food and our bodies. Nutritionism has become a nationally accepted paradigm as to how we view food and what we should eat. Scrinis argues that the “focus on nutrients has come to dominate, to undermine, and to replace other ways of engaging with food and of contextualizing the relationship between food and the body” (39). Scrinis states, “Over the years categories and subcategories of nutrients and biomarkers—such as different types of fats and types of blood cholesterol—have proliferated, promising ever more precise and targeted knowledge and dietary advice” (41). We turn to “functionally marketed foods” that “can be defined as foods that are directly marketed with health claims. These include any marketing claims that refer to the relation between a food or nutrient on the one hand, and a bodily process, disease, biomarker, or state of physical or mental health on the other” (Scrinis, 45). Nutritional reductionism becomes a “kind of nutritional determinism, in which nutrients are considered to be the irreducible units that determine bodily health” (Scrinis, 41). This contextualizes the problem of nutritional reductionism and the limitation of peoples social, spiritual, and gender identities in relation to food.

We need to take a critical standpoint in our views of health, well-being, and disease. There needs to be a shift away from medical approaches and public health morals of blaming and victimizing individuals for their “choices” or actions taken, to an approach that examines the larger social, cultural, and global factors that influence health. Wiedman claims that “efforts at multiple levels should empower communities and leadership” with knowledge of health and disease that is “presented in understandable and culturally appropriate ways to (a) influence accessibility to affordable and healthy choices of foods in local communities; (b) enhance activity levels with designs of transportation systems, work, exercise and recreational facilities; and (c) promote the redevelopment of local food production lifestyles in communities that want to farm, garden, ranch, hunt or fish” (Wiedman 53). This would promote “healthy communities” and address “the necessary structural changes”, in order to “reduce the pandemic of chronic diseases associated with industrial lifestyle” (Wiedman, 53).

Works Cited:

Dennis Wiedman, 2010. “Globalizing the Chronicities of Modernity: Diabetes and the New Metabolic Syndrome.” In Chronic Conditions, Fluid States: Chronicity and the Anthropology of Illness. Lenore Manderson and Carolyn Smith-Morris, eds. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Pp. 38-53.

Gelya Frank, Carolyn Baum, and Mary Law. 2010. “Chronic Conditions, Health, and Well-Being in Global Contexts: Occupational Therapy in Conversation with Critical Medical Anthropology.” In Chronic Conditions, Fluid States: Chronicity and the Anthropology of Illness. Lenore Manderson and Carolyn Smith-Morris, eds. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers university Press. Pp. 230-246.

Gyorgy Scrinis, 2008. “The Ideology of Nutritionism.” Gastronomica 8(1): 39-48.

http://www.crossfittheclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/paleo_diet_caveman_poster-p228497097265485886t5ta_400.jpg

The “Paleo Diet” is considered to be a way of eating, rather than dieting, and dates back to ancient times, before many of us existed. This diet is based upon the types and quantities of foods that hunter-gatherers once ate. This diet consists of lean meat, seafood, fruits and vegetables. The “Paleo Diet”, which has been adapted through evolution and natural selection, imitates the diet of our hunter-gatherer ancestors—a diet high in protein, fruit, and vegetables, with moderate amounts of fat and high quantities of omega-3 and monounsaturated fats. By modifying our modern ways of dieting to be adjacent with our ancestors’ ways of eating seems to provide health benefits.

In the article “Globalizing the Chronicities of Modernity”, Dennis Wiedman reflects on the responses to the chronicities of modernity. Wiedman portrays the major changes in health by stating, “For most of human history as hunters, gatherers, and agriculturalists, humans maintained an active physical lifestyle that varied with seasonal resources and promoted cardiovascular and metabolic fitness. But for the past five hundred years, since early European imperialism, there have been major changes in everyday life and, in consequence, in health” (38). The author addresses the concept of chronicity, an idea used to explain individual and local ways of life, question public health discourse, and consider the relationship between health and the globalizing forces that influence and/or shape it. Wiedman’s main argument is the “theory of chronicity”, which is developed to “reconceptualize and explain the global pandemic of MetS, by arguing that its underlying cause is the dramatic shift from ‘seasonality’ of hunters, gatherers, and agriculturalists to the ‘chronicities of modernity’” (38). With modernity, we see more results of chronic conditions. Wiedman discusses the association of diabetes with the metabolic syndrome (MetS), and how these chronic conditions have become increasingly prevalent in developed and developing nations. The article documents the effects of modernity by “reflecting the rapidity of the demographic and cultural transition” and how it “portrays the critical juncture of modernity as populations transition from subsistence agriculture to a cash economy, from self-produced foods to store-bought foods, from vigorous household chores to the comforts of household appliances, and from actively walking to riding in cars and trucks” (Wiedman, 42). Contemporary examples of modern lifestyles display the connection between the chronicities of modernity and the increased prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes and MetS. Wiedman’s article also discusses the health consequences in relation to globalization. Wiedman describes globalization as the “intensification of worldwide social relations”, in which “production, distribution, transportation, communication, and financial systems link the local to the global” (45). The “aspects of globalization”, in which individuals interactions and social structures become “more uniform”, are said to “jeopardize health” (Wiedman, 45-46). This article explores the unequal impact of chronic illness and disability on individuals, families, and communities in diverse local and global settings.

Here is a link to a video by Dr. Oz on “The Healthiest Diets”:

http://videos.howstuffworks.com/sharecare-videos.htm

This video looks at diets from around the world, why they work, and how to bring them to your own lives and home. Dr. Oz was featured as the “health expert” on the “Oprah Winfrey Show”. In this video, Dr. Oz proposes that certain countries, which diets consist mainly of whole-grain and legumes like beans and rice, in addition to fruits and vegetables, have the best health. The combination of whole, natural foods found among other countries diets, are suggested to provide better nutrition and lower rates of heart disease, diabetes, and other chronic conditions.

Food practices vary from country to country. There are obvious social, cultural, political, and economic factors that influence our perspectives on health and disease. The article “Chronic Conditions, Health, and Well-Being in Global Contexts” , claims that approaches to health should provide “a more powerful appreciation of context—that is, how environments are shaped by physical, geographical, social, cultural, political, ethno-racial, gender, economic, and class-based systems of enablement and oppression” (238). If we take a critical standpoint and look at these multidimensional factors of social, economic, and political conditions that influence and affect health, we are able to understand these conditions and improve the lives of people with chronic conditions. The ideologies of health and disease have affected the relationship between food and our bodies. Nutritionism has become a nationally accepted paradigm as to how we view food and what we should eat. Scrinis argues that the “focus on nutrients has come to dominate, to undermine, and to replace other ways of engaging with food and of contextualizing the relationship between food and the body” (39). Scrinis states, “Over the years categories and subcategories of nutrients and biomarkers—such as different types of fats and types of blood cholesterol—have proliferated, promising ever more precise and targeted knowledge and dietary advice” (41). We turn to “functionally marketed foods” that “can be defined as foods that are directly marketed with health claims. These include any marketing claims that refer to the relation between a food or nutrient on the one hand, and a bodily process, disease, biomarker, or state of physical or mental health on the other” (Scrinis, 45). Nutritional reductionism becomes a “kind of nutritional determinism, in which nutrients are considered to be the irreducible units that determine bodily health” (Scrinis, 41). This contextualizes the problem of nutritional reductionism and the limitation of peoples social, spiritual, and gender identities in relation to food.

We need to take a critical standpoint in our views of health, well-being, and disease. There needs to be a shift away from medical approaches and public health morals of blaming and victimizing individuals for their “choices” or actions taken, to an approach that examines the larger social, cultural, and global factors that influence health. Wiedman claims that “efforts at multiple levels should empower communities and leadership” with knowledge of health and disease that is “presented in understandable and culturally appropriate ways to (a) influence accessibility to affordable and healthy choices of foods in local communities; (b) enhance activity levels with designs of transportation systems, work, exercise and recreational facilities; and (c) promote the redevelopment of local food production lifestyles in communities that want to farm, garden, ranch, hunt or fish” (Wiedman 53). This would promote “healthy communities” and address “the necessary structural changes”, in order to “reduce the pandemic of chronic diseases associated with industrial lifestyle” (Wiedman, 53).

Works Cited:

Dennis Wiedman, 2010. “Globalizing the Chronicities of Modernity: Diabetes and the New Metabolic Syndrome.” In Chronic Conditions, Fluid States: Chronicity and the Anthropology of Illness. Lenore Manderson and Carolyn Smith-Morris, eds. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. Pp. 38-53.

Gelya Frank, Carolyn Baum, and Mary Law. 2010. “Chronic Conditions, Health, and Well-Being in Global Contexts: Occupational Therapy in Conversation with Critical Medical Anthropology.” In Chronic Conditions, Fluid States: Chronicity and the Anthropology of Illness. Lenore Manderson and Carolyn Smith-Morris, eds. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers university Press. Pp. 230-246.

Gyorgy Scrinis, 2008. “The Ideology of Nutritionism.” Gastronomica 8(1): 39-48.

Friday, February 11, 2011

Sexual Desire

http://gayswithoutborders.wordpress.com/2008/12/03/vatican-opposes-un-resolution-on-universal-decriminalisation-of-homosexuality/

The above religious painting was taken from a site titled “Gays Without Borders”, which is “an informal network of international GLBT grassroots activists working to make the world a safer place for GLBT people, and for full GLBT equality in all aspects of legal and social life”. The painting was added to this site as “a declaration against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity”.

Homosexuality has been a controversial topic researched and discussed for hundreds of years. Jennifer Terry’s article, “Medicalizing Homosexuality”, explores how theories through time were developed as to how and why certain individuals become homosexual. Offense towards the homosexual community dates back to the Judeo-Christian times, as Terry’s article states, “For several centuries, official disapproval of homosexual acts stemmed primarily from Judeo-Christian religious doctrine upon which secular laws proscribing ‘offenses against nature’ were based” (Terry 40). In earlier times, homosexuals were punished for the ways in which they behaved; they were put in jail, psychiatric hospitals, or executed. As seen in the religious painting above, the act of homosexuality is something that is not accepted or presented freely, rather, it is represented as something that is evil or demonic, and looked down upon. Judeo-Christian religions view homosexuality as a sin and disapprove of homosexuals, which in some cases, these considerations still hold true and exist today.

Many thought homosexuality was a problem in society that needed to be removed, in order to protect and sustain societal and cultural values. Fear of the unknown was prompted from lack of knowledge on the concept of homosexuality. In turn, this lead to the medicalization of homosexuality, where people, not only suppressed their concerns regarding homosexuality, but also, turned to doctors for help in how to deal with their sexual desires. Terry affirms these ideas by stating, “But faith in the healing power of medicine was certainly not limited to this group. Many who opposed homosexuality thought modern medicine would yield the most reliable knowledge, and in so doing, be useful in riding modern society of the problem. The growing trust in medicine, held by a wide range of people, was tied to the belief that its practitioners were rational, truthful, and objective, while also caring and compassionate”(Terry 42). In this case, homosexuality was thought to be a sickness and a disease.

Due to these concerns presented by society, medical interpretations were developed to describe homosexuality. The first, “interpreted homosexuality in a naturalistic manner. The naturalists perceived homosexuality to be a benign but inborn anomaly, linked to organic congenital predisposition or to other evolutionary factors. Homosexuality, to them, was a condition of inborn sexual inversion, which caused homosexuals to be neither truly male nor truly female but to have characteristics of the opposite sex” (Terry, 43). The second, “consisted of degenerationists” who “considered homosexuals to suffer from an inborn constitutional defect that manifested itself in sex inverted characteristics and in overall degeneracy” (Terry, 43). Both naturalists and degenerationists “believed one’s constitution was comprised of what we would distinguish as biological and psychological attributes, including moral and intellectual qualities” (Terry, 43). Later, naturalists and degenerationists were contrasted by Sigmund Freud and his psychogenists, who were “regarding homosexuality as a psychogenically caused outcome of early childhood experiences. They considered homosexuality to be a perversion of the sex drive away from the normal object of desire” (Terry, 43).

From the beginning of the 19th century to contemporary times, the acceptance of homosexuality has changed. Scientists and researchers have examined the causes and formed theories regarding homosexuality. In present time, homosexuality appears to be more accepted among cultures and society. In addition, our cultural and societal views and discussions of sex have shifted over the years. Shows such as “Sex and The City” have displayed women speaking freely of their sexual experiences and desires. Set in New York City, the show focused on four white American women and social issues such as sexually transmitted diseases, safe sex, and promiscuity. It specifically examined the lives of women and how they are affected by changing roles and expectations for women.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wn_WHLTK3qI

Here is a description by the author of the above video:

“The FIRST chapter in the QueerCarrie remix narrative.

This is the first of THREE remixes in the Sex and the Remix series. Each season of the original SATC will be remixed to build upon the story established in the previous work. The queering of on-screen relationships are especially important for LGBTQ fans and allies who have so few options of characters to identify with in popular culture.

Due to their constant dissatisfaction with the opposite sex, the women of Sex and the City question their desire, will and strength to continue following the expectations of conventional heterosexuality. They're here. They're queer.

The original show appropriated the language of radical feminist politics only to retell old patriarchal fairy tales.

Why are these women, in all their sexual candor and sexual frankness, abandoning their post-feminist thinking? Or, why is it so easy to use the language of radical feminism but so hard to give up on those patriarchal fantasies?

By editing out existing heterosexual innuendo and male characters, I seamlessly create an alternative narrative not typically associated with the original source material”.

Our society today has become more open to talking about taboo subjects, such as sexuality. In this era of “Sex in The City”, sex scandals, and new sexual enhancement technologies, the critique of sexology is important. Janice M. Irvine’s article, “Regulated Passions”, examines the diagnosis of “sex addiction” and the invention of “inhibited sexual desire” and its social and political implications. The article provides a comprehensive understanding on the construction of these two conditions, as Terry traces the history of our cultural discourses on sex and gender and the hidden power within them. Terry states: "The power of medical ideology in the construction of sexual desire derives from its expansion, its authoritative voice. There must be cultural recognition that desire problems are diseases, with a subsequent adoption of the language and concepts of dysfunction" (327). The medicalization of desire reflects cultural values, which "In our culture, both disease and desire are medical events, individual experiences, and social signifiers. There is no linear relationship between medical ideology and individual behavior" (Irvine, 326). Furthermore, Irvine states, “the existence of inhibited sexual desire and sexual addiction as medical diagnoses ensures that proposed solutions will be individual and structural and cultural.” (Irvine 328) While it is apparent that there are biological causes of disease, it is also important to examine cultural causes and other influences when viewing disease. This is addressed in the article as Irvine states, "The content of medical diagnoses is shaped by social, economic, and political factors" (326).

Overall, I think it is important to recognize these approaches to and regulations on sexual desire. Both of these articles discuss the regulation of desire; Terry’s article discusses homosexuality as it moves through the medical lens, and Irvine’s article presents the construction of ‘hyper’ and ‘hypo’ sexuality in contemporary times. Both articles consider the social production and regulation of desire and analyze the ideologies of desire and how they are constructed. I think it is important to analyze desire in how it is shaped by social, economic, and political factors. The regulation of desire often includes viewing deviant forms of desire as wrong and different from what is constructed as the cultural “norm”. If we are to analyze desire by looking at many influential factors, we would be able to see how desires are culturally constructed and socially produced. Our views need to shift from viewing these desires as disease or deviant from the cultural “norm”, and instead, consider the construction of these ideologies of desire.

Works Cited:

“Regulated Passions: The Invention of Inhibited Sexual Desire and Sexual Addiction”. Janice M. Irvine. In Terry, Jennifer, and Jacqueline Urla. Deviant Bodies: Critical Perspectives on Difference in Science and Popular Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995. Print.

“Medicalizing Homosexuality”. Terry. In American Obessesion: Science, Medicine, and Homosexuality in Modern Sociecty. 1999. University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London.

Thursday, February 3, 2011

Seeing is Believing

Image found at: http://www.isna.org/files/images/pornodoc-754.preview.gif

The drawing above is by Charles Rodrigues. Mr. Rodrigues is a creative artist whose cartoons have appeared many times in Playboy, Stereo Review, and the defunct National Lampoon. I found this cartoon image from The Intersex Society of North America (ISNA) website. ISNA is “devoted to systemic change to end shame, secrecy, and unwanted genital surgeries for people born with an anatomy that someone decided is not standard for male or female” (ISNA). ISNA was founded in 1993 as an effort to support those patients and families who felt harmed by their experiences with the health care system. ISNA evolved into an important resource for these affected individuals, their families, and clinicians who are involved with disorders of sex development (DSDs), in order to improve the health care system and overall well-being for those who suffer with DSDs. Later, ISNA collaborated and supported a new organization, Accord Alliance, to promote a more comprehensive approach to care for those with DSDs. This new nonprofit organization established new ideas on appropriate care for DSD-related health and outcomes to be implemented across the nation. With this new organization in order, ISNA closed it doors, in knowing that its efforts and knowledge will be continued. The cartoon image above represents many of the challenges that ISNA has faced, along with, the arguments discussed in Thomas Laquer’s article “Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud”.

First, I would like to discuss what the term intersex means and its implications. Intersex is the general term used for a variety of conditions under which a person is born with something other than standard male or standard female anatomy. In 1998, the standard treatment for intersex was composed of three components, “First, textbooks and journal articles instructed practitioners to lie to their intersex patients and to withhold information from them about their conditions. Second, otherwise healthy children were being subjected to procedures that risked sexual sensation, fertility, continence, health, and life simply because those children didn’t fit social norms. The third problem was the total lack of evidence—indeed, the total lack of interest in evidence—that the system of treatment was producing the good results intended” (ISNA). This standard of care for intersex patients remains unchanged. Most health care centers still treat intersex patients with this concealment-centered model that recommends misrepresenting critical information and surgically altering healthy genitals. ISNA believes that intersex medicine has not changed because the treatment and the core components are a lot like other realms of modern medicine. It is seen as an issue to change otherwise healthy patients to fix social norms, which comes as hardly unusual in the realm of medicine. In this way, the patient can be pushed to become normalized and reconstructed. The same issues of intersex are presented in Laquer’s article on the body and gender.

The article by Thomas Laqeur claims that ancient representations, in the Renaissance period, characterized sexual differences unlike today’s scientists. The scientists of the Renaissance era continued to progress the field of anatomy, in which “the new anatomy displayed, at many levels and which unprecedented vigor, the ‘fact’ that the vagina really is a penis, and the uterus a scrotum” (Laquer, 79). Thus, the vagina was identified as penis and the uterus as testes. This new model states that, “Seeing is believing the one-sex body. Or conversely. Believing is seeing” (Laquer, 79). Laquer argues that the female sexual organs are homologous to male sexual organs, only inside out; “seeing the female genital anatomy as an interior version of the male’s” (Laquer, 86). In the drawings made during dissections, scientists from Aristotle to Galen identified female genitalia as male genitalia, in which “women’s organs are represented as versions of man’s” (Laquer, 81). This model creates the belief that women and men are represented as two different forms of one essential sex; that women have the same reproductive structure as men. Seeing really was believing for these scientists and they relied on their observations of the body to structure the language and order of the body. This new approach to anatomy and ideology of the body is depicted in the cartoon image above. The doctors rely on the normalization and perfection of the body that is produced by social and cultural constructs (or in this case, Playboy). The image further implies that “truth and progress lay not in texts, but in the opened and properly displayed body” (Laquer, 70). Perhaps the doctors in the image, who represent the modern realm of medicine, are adjusting the socially-challenging anomalies of an intersex patient to fix social norms and reconstruct the body.

Laquer does not think scientists from the Renaissance era were mistaken; however, they performed dissections and recorded what they saw, and believed what they saw. Their drawings, in this way, were correct. Since, at the time, their world view did not allow for a two-sex body, the parts of the body of a male versus a female were identified differently. Through time, it has become politically necessary to create a distinction between men and women. Laquer’s argument destabilizes our modern concept of the sexed body as a static, non-historical entity. Social, political, and cultural beliefs and values have influenced and constructed the ways in which we view our bodies, gender, and reproductive systems. Intersex and ideologies of one-sex bodies are constructed as socially-challenging anatomies in the realm of medicine. It is my hope that we can begin to actively recognize and confront the oppressive nature of social anatomical norms and question the use of medicine. This will help us to construct a conscious dialogue of the meaning of anatomy and the implications of these normalizing procedures.

Sources:

Thomas Laqueur, New Science, One Flesh. Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990. Pp. 63-113.

http://www.isna.org/

Thursday, January 27, 2011

Power and Organization in Medicine: Ayurveda and Biomedicine

“Ayurvedic medicine is all the rage in the west, but it's more than just a passing fad -- in India it dates back many thousands of years. Ancient wisdom it may be but does it stand the test of modern science?”

I am having trouble embedding this video into my blog, so I have included the link to youtube if you are unable to view this video: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2FQfZhO60c

This video explains the practice of Ayurvedic medicine and its applications. The video references that Ayurvedic medicine is not tribal or folk healing, as Western nations would perceive it to be, but that it is a system of medicine on its own. The video gives us insight on how big the business of Ayurvedic medicine is in India and how much people believe in it. It also takes the concept of power and organization in medicine and discusses how Indian authorities regard the system of Ayurvedic medicine. Patient recommendations alone would not be able to convince the medical world, it is the Indian authorities who have the power to make Ayurvedic treatment standardized, and subject it to trials in the same ways as conventional drugs are in biomedicine. Equally important is the videos portrayal of the interplay between Ayurvedic medicine and biomedicine.

I have studied alternative medicine in another anthropology class I have taken, in which we discussed the practice of Ayurvedic medicine. For this class we read a book that introduced the concept of power and organization in medicine. The author states that power in medicine and healing may be compared to other raw materials such as fire, earth, water, and air. They are transformed through domestication, controlled or organized, and exploited for profit, as they are converted into wealth, status, and political power or authority. The author reveals that the “primary resources” of medicine and healing, such as the skills of healers, medicines, and knowledge, have become “secondary resources” as they are researched, certified, institutionalized, commercialized, and constructed by society. To expand our understanding, let’s consider how power in medicine and healing has been controlled, organized, and transformed by society when dealing with Ayurveda.

In the article “Medical Mimesis: Healing Sign of a Cosmopolitan ‘Quack’”, Joan M. Langford discusses how Ayurvedic medicine began to mimic professional biomedicine. The author supports this claim with evidence on the contrast between the “traditional” practice of Ayurvedic medicine and the “new” practice of Ayurvedic medicine. The ancient practice of Ayurveda dealt with human ailments, which continue to affect humans today. Ayurveda, in contemporary times, is trying to adapt to the modernization of humans without losing its observation, intuition, and insight based on ancient philosophy. Current publications make an attempt to convey the relevance of the science of Ayurveda to the need of modern times; however, political and scientific controversies still remain regarding the recognition of Ayurveda in Western nations. Modern medicine is powered by the hegemonic position of biomedicine, which validates a drug or treatment based upon scientific evidence. Furthermore, Western nations appear to have power over determining a drug or treatment’s validation. This hegemony of biomedicine in medical knowledge and practice largely affects the authenticity of Ayurveda. Langford comments on how medical systems are continually modeled after biomedicine with her term of “quackery”, which is “a concept used by medical practitioners and others to discredit medical practices other than biomedicine. Some biomedical doctors consider all Ayurveda to be a kind of quackery, based on a bogus view of the body and dispensing treatment the biological effects of which are scientifically unproven” (25). The power of biomedicine on medical systems is also presented in the article “The Sacred in the Scientific: Ambiguous Practices of Science in Tibetan Medicine” by Vicanne Adams. The author asserts this point by stating, "This assumption in part structures Tibetan views about their own traditions of medicine, often resulting in efforts to make their medicine look and feel the same as what they take to be a uniform and universal ‘Western science’. Others strive to establish the ‘scientific’ natures of things excluded from Western science, in order to establish that their own traditions are equally ‘scientific’" (Adams, 544). Both articles portray this idea that Tibetan medicine and Ayurvedic medicine are based on scientific evidence and principles that may not be understood or validated by Western science or medical practice.

When placed in a different society, alternative medicine, such as Ayurveda, is subject to the hegemonic position of biomedicine, which the practice lacks its scientific justification. Although it remains as the same body of medical knowledge, its treatments and practices are used differently in Western societies and are adapted to fulfill personal needs and desires. As Ayurveda is introduced to a new society, it becomes associated with different discourses and relations of power and control. In addition, as Ayurveda becomes embedded into a different social fabric than that of its country of origin, it becomes perceived differently, and its ideas and practices are adjusted to the new social, political, and economic realms. Thus, Ayurveda loses its recognition of science and authenticity and is incorporated into different hegemonic relations and discourses of power and control.

To understand how or why a particular therapy or practice may be folk at one time or setting, popular in another, and highly professionalized in others, one needs to look at the aspects of rationality in medical tradition. In particular, the aspects of power and organization of medicine need to be addressed. By looking at organization in medicine, one can explore the prevailing patterns within a tradition. There is a need to associate the ideas and practices of medical traditions with the social context in which it was created and practiced. By viewing the social context of health and healing, sectors of health care that determine a practice as folk, professional, or popular, can be adopted to that medical tradition. Although these approaches identify the rationality of a medical tradition, they appear to overlook the economic, political, and ideological foundations that society constructs in health and healing. These influences help to determine which ideas, practices, and traditions will become dominant or marginalized. The roles of medical traditions, like biomedicine and Ayurveda, emerge with the understanding of the coexistence of multiple medical traditions, practices, and thoughts, within cultures and societies.

Works Cited:

Adams, Vicanne. 2001. “The Sacred in the Scientific: Ambiguous Practices of Science in Tibetan Medicine.” Cultural Anthropology 16(4): 542-575.

Janzen, John. Power and Organization in Medicine. 2002.

Langford, Joan M. 1999. “Medical Mimesis: Healing Sign of a Cosmopolitan ‘Quack’.” American Ethnologist 26(1): 24-46.

Tuesday, January 18, 2011

Creating a "Competent" and "Caring" Doctor

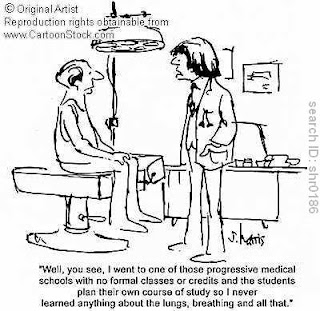

Both images found at: http://www.cartoonstock.com/directory/m/medical_training.asp

Both of the cartoon images above represent the ideas of medical knowledge and training. By providing a glimpse into the practice and curriculum of future physicians, we are surrounded by the idea of creating a “competent” and “caring” doctor, unlike those pictured above. The first image presents the importance of the medical curriculum and how future physicians should or should not be trained. The second image presents the practice of physician and how a physician’s knowledge and training is important in creating a “competent” doctor. In relating these images and both of the articles on “mediating”, I would like to discuss the importance of how medical knowledge is constructed and how the ideologies of health are shaped.

Byron J. Good and Mary-Jo DelVecchio Good’s article “ ‘Learning Medicine’: The Constructing of Medical Knowledge at Harvard Medical School”, studied three groups in the 1990 class at Harvard Medical School, the “New Pathway” curriculum, and the health sciences and technology curriculum. By concentrating on the training of physicians, they believed they could differentiate the “phenomenological dimensions of medical knowledge, on how the medical world, including the objects of the medical gaze—the students and the physicians—are reconstituted in the process, ad how distinctive forms of reasoning about that world are learned” (83-84). The findings of this study are provided in accordance to several themes that encompass medical training, such as:

1. “Medicine is science”. The first two years of the curriculum are emphasized as being science, because medicine is science. Science is factual based and is not affected by or based on value judgments.

2. “The person is the body”. The object of medicine is the individual person, primarily the body.

3. “Medicine is about ‘entering the body’”. Medicine gets inside of the body by case histories and lab exercises.

4. “ ‘Medical gaze’” and its view of the body reconstitute the person as object. In medical training, the student is conditioned to hold the conventional view of the body in a detached manner of seeing the human patient, and to study the view of the person-body.

5. “The ‘medical gaze’ reconstitutes the subject (the student)”. The student has to manage their objective gaze with society’s conventional view of the person-body.

The perspectives of the objective body and the human person, studied by medical students, hold a contradictory message in medical curriculum. The Goods article represents the curriculum as “the dual discourse” of “competence” and “care”. Competence is “associated with the language of the basic sciences, with ‘value-free’ facts and knowledge, skills, techniques, and ‘doing’ or action’” (Good, 91). This part of medicine is given priority because it is presumed as the basis of medical practice. Caring is “expressed in the language of values, of relationships, attitudes, compassion, and empathy, the nontechnical or as one student called it the ‘personal’ aspects of medicine” (Good, 91). This dual discourse creates a progression of dichotomies surrounding the qualities and problems of medical education on how to create “caring” and “competent” physicians.

In the article “Against Global Health? Arbitrating Science, Non-Science, and Nonsense through Health”, the author Vicanne Adams offers a “critical exploration of the processes by which the notion of ‘health’ in Global Health Sciences holds a tyrannical relationships to problems within the actual practices of global health” (40). The author argues that the conversations of “health” between doctors, patients, and politicians are not all talking about the same thing, in which the recognition of “health” is culturally constructed and socially sustained. The author gives us insight on the boundary between “science” and non-science”. In addition, the author discusses the debate on health in two ways. First, the author presents the cultural meanings of health and examines the ideologies that construct its meaning. Second, the author presents approaches in how to move forward, and to discover the principles behind “health”, in order to produce healthier interactions about our bodies.